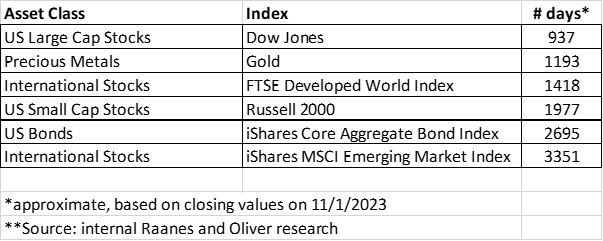

Investors (self-included) are beginning to gripe about how long it’s been since we’ve seen actual gains in ANY broad class of investments. Most major indices are in the exact same spot as they were a few years ago. In the case of the bond market, the broad bond index (as measure by the iShares Core Aggregate Bond Index) is trading at the same level it was in June of 2016. The Emerging Markets index takes the cake though… that index is at the same price level as 2014. For most indices, it’s been a long time without sustained price appreciation. In fact, here is a sobering chart showing the number of days that have elapsed between the current level and the last time we saw these levels.

This is what a “sideways” market feels like...frustrating. It’s unfortunate (and somewhat rare) that virtually all major asset classes are in the same sideways predicament.

Bonds continue to struggle

The bear market in bonds is now the longest and largest in history lasting 39 months (and counting). There is, however, a glimmer of hope emerging that perhaps the Federal Reserve is done with the rate hikes that began in March 2022. If so, bonds could offer some attractive returns over the coming years. The starting point for yields (5-7%) is the most attractive that we’ve seen in 15 years and there is a potential for price appreciation if interest rates begin to decline over the next year.

Which would you rather own?

To further my argument that US bonds may be nearing a turning point, I pose the question, which would you rather own: a 10-year US Government Bond yielding 4.89% or a 10-year Vietnamese Bond yielding 3.02%. Sure, the US has a growing debt burden, but let’s keep it in perspective. Yields in the US are attractive compared to other countries and compared to historical averages. Don’t avoid bonds just because of the recent struggles. I believe brighter days are ahead for bond investors.

Why are rates so high anyway?

The Fed has been increasing interest rates in an effort to fight inflation. Logic suggests that when interest rates are high consumers are generally slower to buy “big-ticket” items like houses and cars and furniture. Correspondingly, businesses are less likely to borrow money to expand operations. Higher rates generally lead to a slower economy, which generally leads to lower inflation. Which is exactly what the Feds are forecasting over the next several years.

If we see a slowing economy, it would also reason that we should eventually see lower interest rates. Which the Fed is also forecasting. Are we seeing signs of a slowing economy? Yes. Keep reading.

Tough for Some

Six percent of subprime car owners (those with low credit scores) are delinquent on their car payments. That may not sound like a large percentage, but it’s already a higher proportion of delinquencies than we saw in previous recessions… even higher than 2008. If we begin to see job losses pick up (more on that in the next chart) or an actual recession (we’ve been expecting it for a year now) we would likely see this ratio move even higher. This is also a little concerning because it speaks to the lack of strength in the lower-end consumer. And let’s not forget the reimplementation of student loan payments began in October and will mean somewhere in the neighborhood of $350-$400 per month for the average borrower (Source: Strategas Washington Policy Research).

Speaking of job losses…

The unemployment rate is still exceptionally low (currently 3.9%), but it is half a percentage point higher than the low point in April. This 0.5% increase in unemployment has historically been an early indicator that a recession is near… very near in most cases. Check out the chart below.

What does this tell us?

Let’s put the pieces together:

1- The Fed wanted to fight increased inflation by raising rates to slow down consumption (starting in early 2022)

2- Consumption didn’t slow as fast as expected so they raised rates more (throughout 2022 and 2023)

3- Consumption finally slows and real estate transactions have ground to a halt (last 6 months)

4- Delinquencies are increasing in car loans, credit cards and consumer loans due to high rates (last 6 months)

5- The unemployment rate is ticking higher as the employment landscape weakens (last 6 months)

6- Inflation expectations have come down and the Fed is signaling for lower interest rates over the coming 24 months

All signs would indicate that the economy is entering a slowdown. My hunch is that a recession isn’t too far away. Strangely, there is still a chance that we get a market rally in the near term in response to expectations of declining interest rates in the future (lower rates have historically been good news for stocks). I suspect that “bad” economic data will be construed as good news for stocks as it feeds into the narrative that interest rates hikes are over. Eventually, the pendulum will swing the other way as the “bad” data continues and recession fears creep in.

At the moment, I stand by the general stance that we’ve kept for the last several months. I’m hard-pressed to see compelling reasons to take additional risk while conservative allocations generate adequate returns. At this point, I tend to see market rallies as opportunities to take profits rather than the beginning of a larger bull market trend.

Every investor's situation is unique and you should consider your investment goals, risk tolerance and time horizon before making any investment. Prior to making an investment decision, please consult with your financial advisor about your individual situation. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. You should discuss any tax or legal matters with the appropriate professional.

The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market.

Bond prices and yields are subject to change based upon market conditions and availability. If bonds are sold prior to maturity, you may receive more or less than your initial investment. There is an inverse relationship between interest rate movements and fixed income prices. Generally, when interest rates rise, fixed income prices fall and when interest rates fall, fixed income prices rise.

The foregoing information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete, it is not a statement of all available data necessary for making an investment decision, and it does not constitute a recommendation. Any opinions are those of Brady Raanes and not necessarily those of Raymond James.